February was another locked down month with a curfew in Quebec, and I was at home going nowhere. It snowed a lot. I saw a total of three other human beings in the whole month. The prevailing mood of this pandemic for many of us is “other people have it worse, but this sure sucks.” I read a perfectly reasonable seventeen books, and many of them were really excellent, which is always cheering.

Fanfare for Tin Trumpets, Margery Sharp (1932)

This is the story of a young man with enough money to live on in London for a year and try to write, who entirely fails to achieve anything. It’s a comedy, though it is very sad, and you can see here the beginnings of the class consciousness which will make so much of Sharp’s later work so excellent. I enjoyed reading it, though I wouldn’t call it good, exactly. It also surprised me that it was 1932; it’s much more a book of the 1920s in feel. For Sharp completists, I suppose. Don’t start here. But I am excited to have so much new to me Sharp available as ebooks.

The Element of Lavishness, Sylvia Townsend Warner and William Maxwell (2000)

Bath book. Letters between Warner and Maxwell when he was editing her work for The New Yorker and after, so we have here the record of a whole friendship from 1938-78. I adore Sylvia Townsend Warner as a person, and I became increasingly fond of William Maxwell as this book went on. We have letters about her work, about his work, about writing, about their lives, their vacations, the birth of Maxwell’s daughters, the death of Warner’s partner, about world events… reading this collection feels like living with the two of them, across decades, or eavesdropping on delightful writer conversations. Highly recommended, just wonderful, wish there was an ebook.

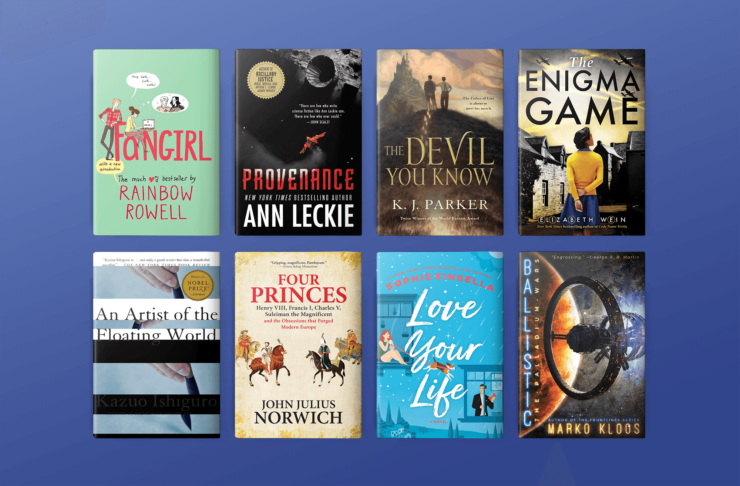

Love Your Life, Sophie Kinsella (2020)

Two people meet at a writing retreat in Italy and fall in love, then they go back to London and discover that they don’t know anything about each other’s real and complicated quotidian lives. This book is very funny, and also touching, and the characters—including the memorable friends and minor characters—are all really well drawn. Despite the publishers trying hard to put me off for years with utterly unappealing covers, I am completely converted to Kinsella and have now bought all her books.

Ballistic, Marko Kloos (2020)

The second Palladium Wars book, just as good as the first one, and now I will have to wait until August for the next one. So far these two books have been very enjoyable set up, and while I think he’s really upped his game from the Lanky books (which I also enjoyed) I hope the payoff is going to be worth it when we find out what is actually going on.

Half Share, Nathan Lowell (2007)

Sequel to Quarter Share. Not enough trading and too much—I don’t even know what to call it. Female gaze? Our first person hero being the focus of female desire. Reads kind of weirdly—and the whole fantasy shopping sequence doesn’t quite make logical sense. Oh well. There’s a spaceship, and space stations, and the first book was a lot better. Nevertheless, having bought the next book I’ll read it and see if it’s going anywhere more interesting.

The King Must Die, Mary Renault (1958)

Re-read, read aloud by a friend in a group of friends. It’s great listening to a book I know as well as this one, and it was also great sharing this with other friends who had not read it before and did not know what to expect. I’ve written about this book before, a very formative and early read for me, arguably fantasy, the first-person account of the life of Theseus, of minotaur fame, who truly believes himself to be son of the god Poseidon. One of the first books to deal with myth this way.

An Artist of the Floating World, Kazuo Ishiguro (1986)

Early Ishiguro, beautiful example of how to convey a story in negative space. This is a story of post-war Japan, and an artist who was associated with imperialism and is in a weird and fascinating kind of denial, as unreliable as narrators get. Really well written, really powerful, a little bleak.

Brunetti’s Cookbook, Roberta Pianaro (2009)

Don’t bother. This is a very odd book, excerpts of many food bits from many of Donna Leon’s Brunetti books, with some unexciting Italian recipes which have nothing to do with them really. However, it made me really want to read Donna Leon. One of my few disappointments this month.

The Enigma Game, Elizabeth Wein (2020)

Best new Wein since Codename Verity. I couldn’t put it down. WWII, Scotland, a great cast of diverse characters, an enigma machine, no romance, and very, very readable. If you haven’t read any of Wein’s recent YA WWII novels, start with Code Name Verity which is amazing, but they’re all very good, and I enjoyed this one no end. I thought from the title this was going to be about Bletchley, which I’ve read a lot about, but not a bit of it. The bulk of the book is set in Scotland and one of the major characters is a West Indian girl.

Provenance, Ann Leckie (2017)

An odd coming-of-age story on the edge of the Ancilliary universe. There was a lot that was great about this book, notably the worldbuilding and the cultures, but I could not warm to the protagonist, which made it less fun than it otherwise would have been. I liked the other characters, but that only goes so far. Great aliens.

The Devil You Know, K.J. Parker (2016)

Brilliant, clever, sly novella about an alchemist signing a contract with a devil, from the devil’s point of view. Loved it. So if I loved this and I loved Sixteen Ways to Defend a Walled City but I found the second Bardas Loredan book too strong for my stomach, what Parker should I read next?

Always Coming Home, Ursula K. Le Guin (1985)

Re-read, but I hadn’t read it for a long time, and I read the new Library of America edition with extra material. I have never liked this book, because it isn’t a novel and it doesn’t have a story—the whole point of it is that they are a culture without a story, and that’s interesting, but… also boring. It’s a great culture. I’ve joked that it should be a roleplaying sourcebook, but it wouldn’t actually be a good one, because there are no stories and so nowhere to go with it. It’s beautifully written, it has flashes of being wonderful, but it isn’t a whole thing.

I was deeply disappointed with this book in 1986 (it was published in the UK the week I graduated from university) and I have been puzzled by it ever since. Is it me, wanting it to be something it isn’t and not being able to appreciate what it is? Is it Le Guin being tired of adventure plots and experimenting with what you can do without one? If so I think it’s a valiant but unsuccessful effort, at a time when nobody else was thinking about this at all within genre. I don’t know. I like bits of it, but I am still unsatisfied with it as a whole thing.

The Music at Long Verney, Sylvia Townsend Warner (2001)

Bath book. Twenty short stories that are absolutely dazzlingly brilliant, all of them, and neither confined to the mundane nor attempting to have adventure plots. I just want to read all of Warner and see her work whole, because she wasn’t like anyone else, and these glimpses are wonderful. I wish there were more ebooks, and in the absence of them I have ordered some more paperbacks to read in the bath until my toes wrinkle up, the way I did with this one.

Fangirl, Rainbow Rowell (2013)

Re-read. This is a very clever book, in which Rowell gives us the story of a fanfic writer going to college, interspersed with excerpts from the original books whose universe she is writing in, and her own fics, and all of it held perfectly in tension. There are some serious mental health and abandonment issues, treated very well, and dyslexia, treated very well; this isn’t a lightweight book, but it is excellent, and compellingly readable, and really a lot of fun.

Four Princes, John Julius Norwich (2017)

A multiple biography of Henry VIII, Francis I, Charles V, and Suleiman the Magnificent, who were all contemporaries. So it’s a book about a time and a place, or a set of places, but focused on the lives of the kings. It’s written for the general reader.

I have a bit of an odd relationship with John Julius Norwich. I was taken to a lecture of his when I was in school, and it was the first thing that ever made me excited about history. Also, I know his parents intimately in a literary way, I’ve read so much by and about Duff and Diana Cooper you wouldn’t believe. I’ve even read Diana’s letters to John Julius. But while I want to like his history books I often find them a little facile, just skimming the surface, and this is no different. I kept finding myself thinking “oh yes, this is because of…” something I knew more about, which meant that with the sections on Suleiman, who I knew least about, I felt I didn’t know what was being left out or simplified.

On The Way Out, Turn Out The Light: Poems, Marge Piercy (2020)

A new book of poetry by Piercy, one of my favourite writers. The poems are in sections about nature, old age, love, politics, family, etc. They are very good, biting, and well observed, and the ones about old age very hard. There’s a line in one of the more political poems, “we rejoice in who we are and how we have survived,” and I think that’s the overall note of this collection. I hope there will be more.

The Jewels of Paradise, Donna Leon (2012)

I’d been saving this book. It’s not in her Brunetti series, it’s a standalone. It’s about a music historian from Venice going back to Venice to investigate two trunks of papers belonging to a seventeenth-century Venetian composer. So the book is about her being in Venice investigating a historical and contemporary mystery, reconnecting with family and the city. It lacks the biting wider social consciousness of some of Leon’s work, but right now I didn’t mind the smaller scope here.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published two collections of Tor.com pieces, three poetry collections, a short story collection and fifteen novels, including the Hugo- and Nebula-winning Among Others. Her novel Lent was published by Tor in May 2019, and her most recent novel, Or What You Will, was released in July 2020. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here irregularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal. She plans to live to be 99 and write a book every year.

I own and have read all of Nathan Lowell’s books — and re-read many of them. Having said that, please be aware that the second trilogy is much darker in tone and “Owner’s Share”, especially, is tragic. For something different, maybe try “The Wizard’s Butler”

If you enjoyed Sixteen Ways…then How to Rule an Empire and Get Away With It is a direct sequel and should be up your street. I enjoyed it very much – the author inverts a lot of his own tropes and habits so the ending came as a real surprise to me. I felt like I’d been the subject of a long con, almost.

I do enjoy this column. I always get good recommendations out of it, and I like that it has a slightly broader focus than the rest of the site. Jewels of Paradise sounds like it could be just what I need, and it’s going on my list.

@1. sheila

I loved The Wizard’s Butler. I keep hoping he’ll write a sequel (or two, or three )

)

And, like always, more books to add to my (already too long) “to be read” list.

edited for spelling

Alex: I didn’t like How to Rule an Empire half as much, it was OK, and I enjoyed it, but it didn’t have that extra bounce that 16 Ways and this novella did.

I highly recommend Sharps by KJ Parker. Same setting, focuses on a group of characters thrown together to travel to a rival nation and go on a tour performing something like Nixon’s ping pong diplomacy with China, but with fencing instead of ping pong. It’s my favorite Parker. Another favorite is an epistolary novella called Purple and Black, which is perfect aside from not being a trilogy.

@bluejo: Oh no! Sorry! I feel a bit foolish now.

On the off chance you’re still listening, I thought his novella Mightier Than the Sword had an almost Wodehousian cadence to it.

In fact, I said that to be glib but it has a fearsome aunt, an unfortunate matrimony and well meaning clothhead with old school chums so it might actually have been an actual pastiche

In my opinion, the shorter the Parker works are, the better. Thus, I would get Academic Exercises, which collects some of his best short fiction: “A Small Price to Pay for Birdsong”, a tremendous rewrite of the Mozart/Salieri story; “The Sun And I”, about the creation of the Sun Invictus religion; “Blue and Gold”, with a great unreliable narrator; or “Purple and Black”, the letters between and Emperor and his all college buddy.

His best novel is probably The Folding Knife, although Sharps is also very good and its most “mainstream” work.

Wimsey’s recommendations are very sound — “A Small Price to Pay for Birdsong” is probably my favorite piece of short fiction, and “Blue and Gold” my favorite of his many novella-length pieces. The Folding Knife is a good candidate for his best novel, though I remain partial to the Engineer trilogy.

Once more piece of short fiction, “Told by an Idiot”, which rarely is not set in what we could call “Parkerworld” but instead is a sort of alternate Shakespeare story. Brilliant. It’s in another Subterranenan collection, The Father of Lies.

(I will forebear recommending again The Walled Orchard! :) )

And, finally, recommending “Told by an Idiot” makes me think of Greer Gilman’s two Ben Jonson novellas, “Cry Murder! in a Small Voice” and “Exit, Pursued by a Bear”, from Small Beer Press. Have you read those? They’re great.

I second the recommendations for The Folding Knife and Sharps. Both are probably his most “mainstream” works, easier to swallow to those who find his more “hardcore” novels like Loras Boredan books or The Company too much. And yes, he has written quite a lot of shorter fiction which also can be a mixed bag, but the best of them are excellent.

You might enjoy Prosper’s Demon, which has a Da Vincian character in it, although it’s a bit dark. The protagonist is typically Parkerian – a cynic who tries to do the right thing, despite what it costs him and others.

Agreed on the Renault – ancient Knossos (and Mycenean Greece) really come alive in this and the sequel, The Bull From the Sea, and Theseus is depicted as a relatable character despite being drawn as very much a person of his own time. Something of a trick when writing in the first person. The two books have aged well.

@@@@@ 10

Second the nomination for Prosper’s Demon. The Devil You Know was my intro to Parker, Prosper’s Demon was my most recent. Won’t be my last.

I read the two Renaults when I was in middle-grades — possibly first in Greece. (I remember a tour guide who was very disparaging, partly because she didn’t like the books having even discreet sex in them.) My recollection from way-long-ago thinks they aren’t fantasy — Theseus tends to hear the gods telling him to do what he wants to do anyway — but I wouldn’t try to argue that position rigorously.

I’m not sure about warming to Provenance‘s narrator, but I had a great deal of sympathy for her; she’s trying to find a toehold in a family that thinks she’s of no consequence and doesn’t have the medieval option of discarding her to the Church. This parallels some of my favorite Cherryh, although the maneuvers are subtler.

I don’t remember ever hearing “Elizabeth Wein” as an author’s name before, but I’m going to have to try one even if it doesn’t talk about Bletchley.

@12 –

Renault was quite explicit about these books not being fantasy. Theseus could sense incipient earthquakes (which he attributes to his father Poseidon Earthshaker), but she points out that there’s reason to believe that many animals can do so and simply extends this to some human beings.

I’m so glad you enjoyed BALLISTIC, and I hope that CITADEL will pay some of those expectation dividends when it comes out. (I may know a guy who can set you up with an ARC if you don’t want to wait until August.)

I just added “Element of Lavishness” to my TBR. Since you liked it, you might try “Letters to a Friend” by Diana Athill (letters from her to her editor/friend over thirty years). She was a fascinating woman, witty and a pleasure to read, and it’s interesting to see the decline in quality when she switched from longhand letters to begin using email in its place. When I saw you read her “A Florence Diary”, I was hoping you’d continue with her memoirs. I’ve read all of her nonfiction and loved it, but “A Florence Diary” is definitely not her best and I think you’d like her style.

Donna: I’ve put it on my list, thank you.

Marko: Oh, yes, definitely!

I’ve never read Always Coming Home, but now I’m reminded of that Irish tale about the man without a story, who was given one whether he liked it or not.

What I read in February was Lifelode, by Jo Walton, which I’d never come across before, and which I thoroughly enjoyed.

You could never call it a book without a story — plenty of story happens in it, all very interesting, and joyful, and heartbreaking. But equally as important are all the little domestic stories, love and work and children, and keeping everyone fed and sheltered, even if it’ll all be the same in a hundred years.

Also I read Katherine Addison’s The Angel of the Crows, which is not so much a book without a story as a book with reused stories, there to give the book something to do with its worldbuilding. Recycled Sherlock Holmes is all very well, but I really wanted to know more about the angels and hellhounds and vampires and werewolves. Still, it was a lot of fun.

Speaking of fanfiction, one of these days I’m going to get around to reading Fangirl.

I was so happy to find out about the existence of The Enigma Game, Elizabeth Wein (2020) from you as I loved Codename Verity and had somehow missed out on the publication of The Enigma Game.

Glad to see this article! The King Must Die was my first Mary Renault and I read all of them that I could find. The Mask of Apollo and The Praise Singer remain my favorites.

I still love Always Coming Home: the first time I read it, it was because of the shock resulting from not immediately understanding the cultural mores that were operating. The next time, because the story is about people whose stories are usually overlooked.

I had much the same reaction to Provenance, but many protagonists would be let-downs after Breq.

Looking forward to next month’s round-up.

I love KJ Parker, but the books can be uneven. The Folding Knife is my favorite stand alone, and the Engineer Trilogy is the best series. They won’t disappoint!

I was somewhat lukewarm on Provenance also, which surprised me after I loved the Ancillary trilogy.

Definitely need to look up The Enigma Game. I’ve read Code Name Verity and Rose Under Fire, both were excellent.

MSB: Everyone is a let down after Breq! One of my favorite characters in literature. More Breq!